- SELF STUDY MODULES

- 1. Intro to TBI

- 2. Communication

- 3. Skills for independence

- 4. Cognitive changes

- 5. Behaviour changes

- 6. Sexuality

- 7. Case management (BIR)

- 8. No longer available

- 9. Mobility & motor control

- 10. Mental health & TBI:

an introduction - 11. Mental health problems

and TBI: diagnosis

& management - 12. Working with Families

after Traumatic Injury:

An Introduction - 13. Goal setting

- 13.0 Aims

- 13.0A Take the PRE-Test

- PART A:

SETTING GOALS

IN REHABILITATION

- 13.A1 Goal setting in rehabilitation

- 13.A2 Goals, steps and action plans

- 13.A3 Goal setting in Person centred care

- 13.A4 Person centred/directed planning & goals

- 13.A5 Participation

focus & goals - 13.A6 Effective Goals

- 13.A7 SMARTAAR Goals: Characteristics

- 13.A8 Tips for Funders and Services

- 13.A9 Take home messages

- PART B: TEAMS &

GOALS - PART C: WORKSHEETS

- PART D:

POST-TEST

AND RESOUCES

13.A7 SMARTAAR Goals Characteristics

- SMARTAAR

Goals

- (i) Specific

- (ii) Measurable

- (iii) Achievable

- (iv) Relevant

- (v) Time bound

- (vi) Action plan

- (vii) Achievement rating

- (viii) Reporting

The SMARTAAR Goals

SMARTAAR Goals refers to:

- the development of SMART goals that reflect what' the person wants to achieve

- that are USED in rehabilitation work.

The key steps of a SMARTAAR goal writing process include:

-

Writing a SMART goal

-

Reviewing the goal quality and making refinements if necessary

-

Using goals to support service provision and clinical practice.

Writing a SMART Goal

The first step is to write the goal incorporating as many elements and details as is necessary to describe what the person needs or wants to be able to do. This is done as succinctly as possible, but with sufficient detail so that it is as clear as possible at what point the goal has been achieved.

Using it in Rehabilitation work

The second step is to use the goal in the rehabilitation process (the AAR part of SMARTAAR).

Reviewing the goal against the characteristics of SMARTAAR Goals

The goal and its use can be reviewed by testing it against each of the characteristics of SMARTAAR goals.

Which of the following are person centred SMART goals?

Which of the following could be part of AAR?

Specific

The goal must specify the outcome the person is aiming for.

When goals are specific, the person knows exactly what to aim for, when, and how much.

The goal should include specific terms so it is easy to measure or know when it has been achieved (as much as possible).

Specific goals should describe concrete outcomes rather than abstract or vague outcomes. For example:

‘John will join his friends on a fishing trip’ is specific.

‘John will join his friends on a fishing trip’ is specific.

‘John will increase his social interactions’ is not specific.

‘John will increase his social interactions’ is not specific.

Try hard’ or ‘Do your best’ are not specific.

Try hard’ or ‘Do your best’ are not specific.

Try to get more than 80% correct’ is specific.

Try to get more than 80% correct’ is specific.

Concentrate on beating your best time is specific.

Concentrate on beating your best time is specific.

Goals must be unambiguous and clear.

Sometimes, wordy and lengthy goals can contain so much information the change desired by the person is lost in extraneous detail. Often, simplifying a goal by removing extraneous elements can make it a more effective goal. Consider the person's expressed priorities, impact of injuries, level of functioning and stage in the rehab process.

Context and conditions that are required may need to be included

The context and conditions that are required may need to be included to improve a goal’s specificity. Context generally refers to where the activity will take place e.g.

‘Jack will return to his pre-injury employment as a mechanic with Ford’ is specific

‘Jack will return to his pre-injury employment as a mechanic with Ford’ is specific

‘Jack will return to work’ is not specific enough.

‘Jack will return to work’ is not specific enough.

Context may be implicit. For example, if Jan’s goal is to cook the family’s evening meal, we do not need to specify ‘in her home kitchen’. Conditions generally refer to the level of assistance and equipment required. These elements can also be thought of as increasing a goal’s measurability and are described further in the following section.

Measurable

It must be possible to identify when the goal has been achieved. The goal needs to describe the desired level of performance.

The degree or specificity of ‘measurable’ will often be informed by the person's own expectations, or based on their previous level of participation. The Table below describes elements of a goal that could be used to make it measurable.

Element |

Examples of Measurable Goals |

How much |

|

How often |

|

How well |

|

With what level of independence/ assistance |

|

A goal may only require one of the elements above, or it may require multiple elements.

A goal does not need to include numbers to be measurable.

It is measurable so long as there is no ambiguity about what constitutes achievement of that goal. For example, ‘Melissa will be able to independently brush her teeth’ is measurable - either she can or she can’t.

A meaningful measurable goal can help a person to stay motivated to complete their goals when they have a milestone to indicate their progress.

Measureable and meaningful

In the SMARTAAR Goal Process, any numbers used to quantify or describe when a goal is achieved must also be meaningful. A compromise may be needed between the degree to which a goal is measurable and meaningful.

To support person centred practice, it is most important that goals are meaningful, and measurable enough to support their use in practice.

Steps can often include more ‘measurable’ elements than goals, as these are more clearly linked to service provision, as long as the goal itself is clearly linked to the person's desired level of change.

The level of measurement needs to be balanced with ensuring the goal remains clear and is easily understood. While numbers can provide clear indicators for goal attainment, they do not always help make a goal measurable and can reduce the meaning of the goal for a client e.g. ‘74% community integration’, ‘change on assessment from 50 to 65 points’. Referring to change in scores on objective measures is rarely relevant to the person, although it may be useful tool for the clinician to monitor the client’s progress.

For example,

![]() ‘Jack’s anxiety while playing golf will improve by 5 points on the anxiety scale’

‘Jack’s anxiety while playing golf will improve by 5 points on the anxiety scale’

![]() ‘Jack will enjoy playing golf once a week’.

‘Jack will enjoy playing golf once a week’.

Quality of performance

The quality of performance can sometimes be implicit. To use the previous tooth brushing example, we do not need to specify ‘using the correct amount of toothpaste, not missing any teeth and remembering to spit out rather than swallow the toothpaste’, even though these are elements we would consider when determining goal achievement.

However, these nitty-gritty elements of a goal become relevant when a goal has already been worked towards and has been almost achieved. For example, if Jason’s goal is to return to his pre-injury job as a motor mechanic and he achieves this in every aspect other than the fact that he is consistently late to work, the next goal would be ‘Jason will be on time to work each day.’

Jack will increase his contribution to family life

Jack will increase his contribution to family life

Jill will improve her balance and mobility

Jill will improve her balance and mobility

Jack will experience improved mood

Jack will experience improved mood

Jill’s comprehension will improve

Jill’s comprehension will improve

Jack will increase his community participation

Jack will increase his community participation

Achievable

Ideally, goals should be achievable but challenging.

There is a balance that needs to be aimed for when setting a goal so that it is sufficiently achievable so as not to be intimidating, yet challenging enough to be motivating

However, in some situations you may want to document the person's goal, even when it is unrealistic.

The ‘gap’ between the current action plan and the person's goal can inform ongoing discussions with person to support the development of insight, particularly if progress towards goal achievement is much slower than the person anticipated. It can also be useful to document unrealistic goals to highlight service gaps where services are unavailable or inadequate.

As a practical tip goals set to be achieved within a shorter time frame, say 3-6 months or less, should be ‘probably attainable’, whilst longer term and life goals will be ‘possibly attainable’.

The degree to which a client generated goal is achievable will vary. When clients are unrealistic, the the service provider or clinician may need to identify client focused (not client generated) goals that are useful for that stage of the rehabilitation program. Incorporating client generated goals as well can be useful to indicate the ‘gap’ between what the client and service provider or clinician are aiming for in the foreseeable future. It also serves to describe potentially longer term client priorities.

Relevant

It is of primary importance that the goal is relevant to the client.

The client needs to be able to answer ‘yes’ when asked,

- ‘Is this goal something you want to work towards?’,

- ‘Is this goal important to you?’,

- ‘Does this goal matter to you?’

This aspect of writing a goal is consistent with a person centred approach. A goal that describes how the person wants to change will usually be relevant to them.

The likelihood of goal achievement is increased when the client goal is relevant to the service provider. It is useful to identify whether the service can provide the required intervention to achieve the goal.

However not every client goal will be relevant to specific services or funders. This needs to be documented and actions may be limited to making referrals or seeking alternative funding opportunities e.g. where the goal is not directly related to injury, is complicated by a pre-existing condition or is outside legislative boundaries of the primary scheme.

At times it can also be useful to record goals that cannot be achieved due to such constraints to highlight service gaps.

Time-bound

When will the goal be realistically achieved? Without a time frame, there is less urgency to start taking action towards achieving the goal.

This is best specified by a date, rather than by a length of time e.g., ‘by February 2013’, rather than ‘in 3 months’ time’.

This prevents the need for constant referral back to when the goal was written and makes it clearer as to whether or not client progress is on track.

The time-frame for a rehabilitation plan should be guided by how long it is likely to take to achieve the identified goals, rather than formulating goals to fit in with a predetermined plan period. The individual circumstances of each client will impact on the time needed to achieve a goal. It will still be necessary, of course, to specify an approximate time frame with the client when engaging them in conversations about what their goals are i.e. whether you are asking them to identify a goal for the next 3 - 6 weeks or the next 3 - 6 months.

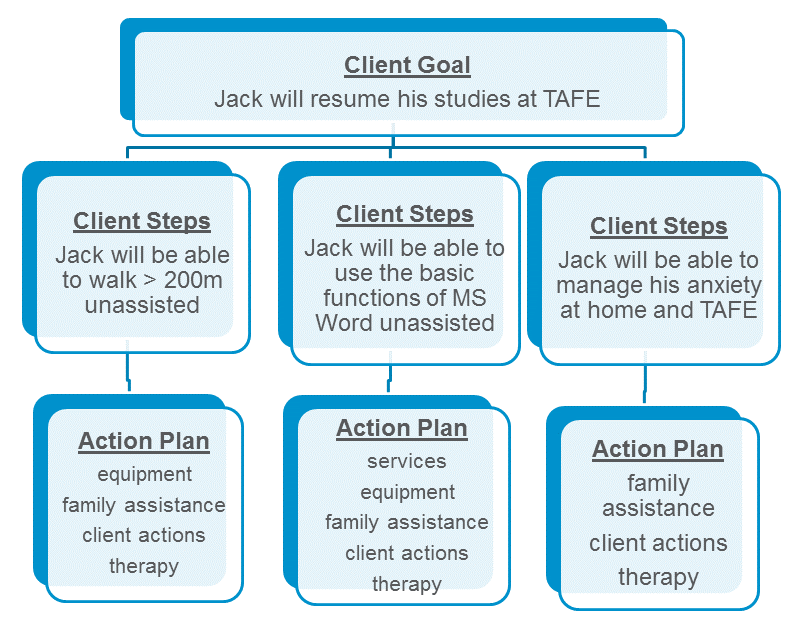

Action Plan

The action plan specifies each activity / behaviour that will contribute to achieving the steps.

The steps are sub-goals to achieve the overall goal.

These activities in the action plan may need to be performed by the client, service provider or clinician, family member or carer. The action plan is intentionally separate from the client goal statement to differentiate that what the client wants to achieve is not the same as the intervention the clinician wants to provide. The action plan describes what needs to be done to enable the client to achieve their goal – these are related but separate elements of the rehabilitation plan.

Achievement Rating

Goal achievement needs to be measured if goals are to be useful in rehabilitation work.

Progress towards the achievement of both goals and steps, and the delivery of the action plan should be measured (and then reported / shared).

Assessing the client's progress in this way enables the goal to be used as an outcome measure. This also allows reporting of the reasons for not achieving the goal or step, as well as the identification of any issues that affected client progress and the implementation of the action plan.

There are many methods of rating achievement, some more complex than others. Rating scales can include achieved, partially achieved, not achieved, over achieved and discontinued.

The key is that some method of measuring goal achievement is used to ensure that the purpose of the goals is met.

Here are some examples of achievement rating scales.

Goal Achievement: Example of a 5 point rating scale |

|

1 |

Not achieved |

2a |

Partially achieved |

2b |

Mostly achieved |

3 |

Achieved |

4 |

Achieved + |

|

|

Goal Attainment Scale (GAS) |

|

+2 |

Much better than expected |

+1 |

Better than expected |

0 |

Expected |

-1 |

Less than expected |

-2 |

Much less than expected |

When using the GAS, the specific outcome that would constitute each score is determined at the time the goal is set. The GAS is recognised as being very effective as a measure of rehabilitation outcomes, but can be very time consuming.

Measuring goal achievement is only useful when the goal describes how the person will benefit.

Reporting Goal Outcomes

Goal outcomes need to be reported to make them useful.

Who and how progress needs to be reported will depend on the purpose and stakeholders involved.

Consider who needs to know this information - the client and their family, service provider, rehab team, other agencies?

Clients and families may want informal verbal feedback, but sometimes written feedback can be powerful.

Service provider and clinician team members will need timely feedback on client progress and the client’s views on their feedback.